What happens when an economy stops growing, but life continues to improve? Japan may already have the answer. For over three decades, Japan’s economy has barely moved. Growth flatlined, prices stayed low, and interest rates were cut to zero. Yet, the country didn’t fall into chaos.

Instead, Japan built something strange and quietly radical. It remains the world’s fourth-largest economy. Unemployment is low, education levels are high, and people live long, healthy lives. Chandrima Banerjee, writing in The Times of India, asks: “What if this seemingly stagnant economy isn’t a cautionary tale, but a glimpse into humanity’s future?”

When growth stopped, life didn’t

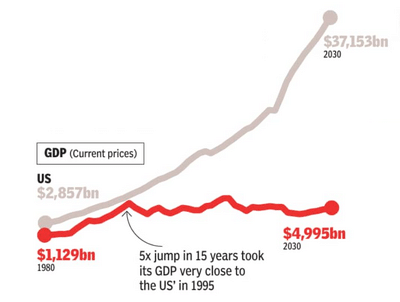

In the 1980s, Japan was seen as a global powerhouse, often called the “relentless Japanese economic juggernaut.” America and Europe saw it as a rising threat, not unlike how they now talk about China. Then, the miracle slowed. After a dramatic rise, Japan’s GDP peaked close to America’s in 1995 and has since inched forward. In current prices, it went from $1.1 trillion in 1980 to $5 trillion by 2030, while the US soared to $37 trillion.

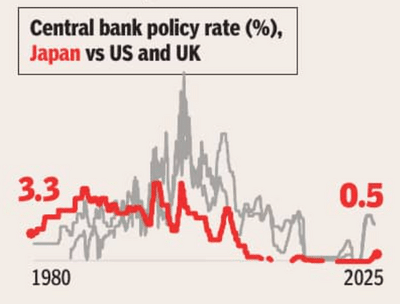

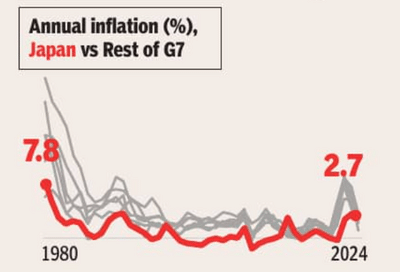

Since the 1990s, Japan has lived with near-zero inflation, falling prices, and interest rates that hovered near or below zero. The Bank of Japan introduced zero interest rates in 1999, then pushed them into negative territory in 2016. That policy stayed in place until 2024. Even now, borrowing remains cheap.

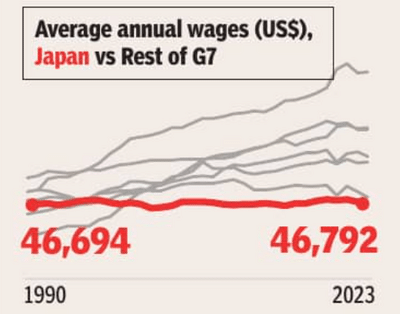

But if prices didn’t rise, neither did wages. Workers stopped expecting raises. Companies stopped offering them. “Deflation left lasting habits,” the report notes, and those habits stuck. Average annual wages barely moved between 1990 and 2023, from $46,694 to just $46,792.

Cautious spending, cautious living

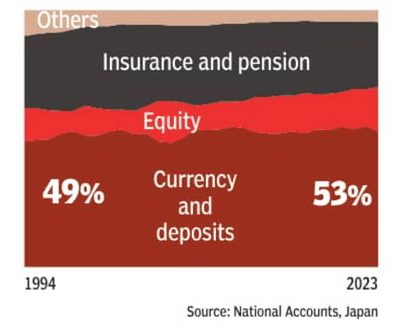

Living longer has made Japanese households more careful with their money. Real household spending rose only about 20 percent in three decades. People now spend more on healthcare and insurance, less on travel or shopping.

Instead of investing, they save — mostly in cash. Nearly $15 trillion in household financial assets sit in bank deposits or physical currency. Half of all Japanese savings are held this way. That has a cost. “That much idle capital means less flows into productive investment,” the analysis points out.

No job hopping, no pay jumping

The labour market is frozen in other ways too. Quitting a job is rare. In early 2025, only 17 percent said they wanted to change jobs. Of those, 63 percent weren’t even looking. Just 5 percent actually made the switch.

Why? The system rewards long-term employment. The longer you stay, the better your pay and benefits. But if you leave, you often end up in what’s called “irregular” work. Today, 48 percent of Japanese workers hold such jobs, which typically offer lower wages and fewer protections.

That’s why mobility is low, and with that, wage growth suffers. Since the late 1980s, job change rates have barely moved — from 2.9 percent in 1984 to just 4.8 percent in 2025.

Ageing before the world does

Japan is ageing faster than almost any other country. Its fertility rate has not touched replacement levels since 1974. Today, it stands at 1.21. The birth rate is just six per 1,000 people, a quarter of what it was in the 1950s. Life expectancy hovers near 85. The median age has risen to 49.

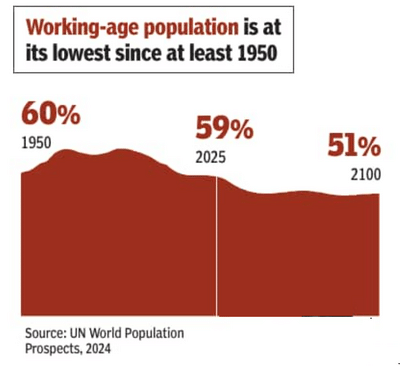

Older people now make up a large part of the workforce. In the 1960s, just 8 percent of workers were 60 or older. Now, it’s nearly 22 percent. Meanwhile, the share of the working-age population has dropped to its lowest since at least 1950.

Other countries are not far behind

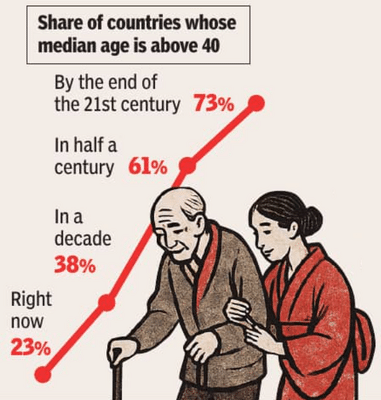

UN projections suggest that 94 percent of the world’s countries will have fertility rates below replacement by the end of this century. The share of nations with a median age above 40 is expected to rise from 23 percent today to 73 percent by 2100.

Many of these countries are already showing Japan-like patterns. Greece and Italy now have more workers staying in the same job for over a decade than Japan. Greece and Poland also have more people storing wealth in cash than Japan does.

So far, immigration has delayed some of the effects. But Japan remains nearly closed, with migrants making up just 3 percent of its population. If other countries also close their doors, they may face the same demographic crunch.

Slower growth, but still living well

Despite this, Japan has not unravelled. It has built a society that works with low growth. Life expectancy is among the highest. A 65-year-old woman in Japan can expect to live another 24.7 years, compared to 20.7 in the US. Two in three young adults have a college degree. And unemployment is just 2.6 percent.

Welfare also holds up. “Today in Japan, a jobless couple with two children can expect to exit poverty with 26 hours of weekly work on minimum wage,” writes Banerjee. “In the US, they would need 80 hours.” If that same couple lost their jobs, unemployment benefits would cover 69 percent of their past income. In the US, the figure is 36 percent.

The OECD says, “Lower growth can have advantages — when it is the result of societal consensus.” Japan didn’t plan it this way, but decades of preparing for a slower, older world may have helped it adapt.

It is not a country without problems. But it has managed to create stability without chasing endless expansion. For nations facing population decline, social ageing, and economic uncertainty, Japan might be a warning. Or it might be a working model of how to live well when growth slows.

Instead, Japan built something strange and quietly radical. It remains the world’s fourth-largest economy. Unemployment is low, education levels are high, and people live long, healthy lives. Chandrima Banerjee, writing in The Times of India, asks: “What if this seemingly stagnant economy isn’t a cautionary tale, but a glimpse into humanity’s future?”

When growth stopped, life didn’t

In the 1980s, Japan was seen as a global powerhouse, often called the “relentless Japanese economic juggernaut.” America and Europe saw it as a rising threat, not unlike how they now talk about China. Then, the miracle slowed. After a dramatic rise, Japan’s GDP peaked close to America’s in 1995 and has since inched forward. In current prices, it went from $1.1 trillion in 1980 to $5 trillion by 2030, while the US soared to $37 trillion.

Since the 1990s, Japan has lived with near-zero inflation, falling prices, and interest rates that hovered near or below zero. The Bank of Japan introduced zero interest rates in 1999, then pushed them into negative territory in 2016. That policy stayed in place until 2024. Even now, borrowing remains cheap.

But if prices didn’t rise, neither did wages. Workers stopped expecting raises. Companies stopped offering them. “Deflation left lasting habits,” the report notes, and those habits stuck. Average annual wages barely moved between 1990 and 2023, from $46,694 to just $46,792.

Cautious spending, cautious living

Living longer has made Japanese households more careful with their money. Real household spending rose only about 20 percent in three decades. People now spend more on healthcare and insurance, less on travel or shopping.

Instead of investing, they save — mostly in cash. Nearly $15 trillion in household financial assets sit in bank deposits or physical currency. Half of all Japanese savings are held this way. That has a cost. “That much idle capital means less flows into productive investment,” the analysis points out.

No job hopping, no pay jumping

The labour market is frozen in other ways too. Quitting a job is rare. In early 2025, only 17 percent said they wanted to change jobs. Of those, 63 percent weren’t even looking. Just 5 percent actually made the switch.

Why? The system rewards long-term employment. The longer you stay, the better your pay and benefits. But if you leave, you often end up in what’s called “irregular” work. Today, 48 percent of Japanese workers hold such jobs, which typically offer lower wages and fewer protections.

That’s why mobility is low, and with that, wage growth suffers. Since the late 1980s, job change rates have barely moved — from 2.9 percent in 1984 to just 4.8 percent in 2025.

Ageing before the world does

Japan is ageing faster than almost any other country. Its fertility rate has not touched replacement levels since 1974. Today, it stands at 1.21. The birth rate is just six per 1,000 people, a quarter of what it was in the 1950s. Life expectancy hovers near 85. The median age has risen to 49.

Older people now make up a large part of the workforce. In the 1960s, just 8 percent of workers were 60 or older. Now, it’s nearly 22 percent. Meanwhile, the share of the working-age population has dropped to its lowest since at least 1950.

Other countries are not far behind

UN projections suggest that 94 percent of the world’s countries will have fertility rates below replacement by the end of this century. The share of nations with a median age above 40 is expected to rise from 23 percent today to 73 percent by 2100.

Many of these countries are already showing Japan-like patterns. Greece and Italy now have more workers staying in the same job for over a decade than Japan. Greece and Poland also have more people storing wealth in cash than Japan does.

So far, immigration has delayed some of the effects. But Japan remains nearly closed, with migrants making up just 3 percent of its population. If other countries also close their doors, they may face the same demographic crunch.

Slower growth, but still living well

Despite this, Japan has not unravelled. It has built a society that works with low growth. Life expectancy is among the highest. A 65-year-old woman in Japan can expect to live another 24.7 years, compared to 20.7 in the US. Two in three young adults have a college degree. And unemployment is just 2.6 percent.

Welfare also holds up. “Today in Japan, a jobless couple with two children can expect to exit poverty with 26 hours of weekly work on minimum wage,” writes Banerjee. “In the US, they would need 80 hours.” If that same couple lost their jobs, unemployment benefits would cover 69 percent of their past income. In the US, the figure is 36 percent.

The OECD says, “Lower growth can have advantages — when it is the result of societal consensus.” Japan didn’t plan it this way, but decades of preparing for a slower, older world may have helped it adapt.

It is not a country without problems. But it has managed to create stability without chasing endless expansion. For nations facing population decline, social ageing, and economic uncertainty, Japan might be a warning. Or it might be a working model of how to live well when growth slows.

You may also like

QatarEnergy releases August fuel prices: Diesel up, petrol unchanged, see latest rates

Jerusalem Biblical Zoo worker fighting for life after horror leopard mauling

SIR in Bihar: EC releases draft electoral rolls; claims and objections open till September 1

'I wondered how big my coffin would be - it made me lose 11st in 18 months'

New Rules: From UPI to LPG gas prices... what will change from today; Know the answer to every question here